More than 60 countries are heading to the polls this year, and in some countries, elections pose the risk of exacerbating polarisation. Our Founder & Director Thania Paffenholz reflects on how national dialogues might complement elections as a means to address societal and political tensions.

Author: Thania Paffenholz

More than half the world’s population is voting in elections this year, making 2024 the biggest election year in history. At the same time, the world is in a state of extreme polarisation both between states and within states and elections have become a barometer for this polarisation. Sometimes, holding elections is the right thing to do to address polarisation. But sometimes elections only exacerbate polarisation and a national dialogue or governments that unite different sides might be better placed to address the societal and political tensions in a country.

When you have extreme polarisation and an election law that favours a “winner takes it all” approach, like in the US, then elections manifest the divide and exacerbate the polarisation. To address the divide, a national dialogue or an election accompanied by a national dialogue could be better placed. In short, national dialogues allow all voices in a population to be heard, allowing the government to address grievances and concerns with members of civil society and political opponents.

In France for example, years of protest over contested reforms by the ‘yellow vest’ movements and others, were followed by a national dialogue in 2022, with members from all parts of French political and civil society to “address some of the country’s most pressing problems”. The dialogue might not have had the wanted outcome – but the strategy applied was well-suited to address polarisation.

In France, the electoral law favours coalitions and in such systems, elections could lead to a shift away from polarisation. When an electoral system allows for coalitions it can go in two directions. Either all parties from one camp form the government and polarisation cannot be addressed or, parties from grand coalitions form a government of national unity, as just seen in South Africa, which has a better potential to allow for addressing polarisation.

Beyond the temporality of elections, the electoral system can significantly affect the opportunities for dialogue. In systems that require a party or a coalition to win an electoral majority, there is more incentive to build even a modicum of consensus, whereas systems that are driven by a “winner takes all” approach fundamentally lack incentivization or even the possibility for political parties to build consensus. In South Africa, the elections presented a chance to address polarisation.

However, the picture could be different in countries where the electoral systems presents itself as a “the winner takes it all” system. In these electoral systems, elections might become powerful catalysators for polarisation.

This trend is evident in countries like Turkey and India, where electoral outcomes are often decided by narrow margins. In the United States, the situation is particularly notable, where the candidate who receives fewer popular votes can still win the presidency due to the electoral college system.

So if not elections what then? Instead of answering, I would rather pose the question: When do elections in polarised societies increase or decrease societal and political tensions and under which circumstances do election makes sense and under which circumstances elections could better be replaced or complemented by national dialogues or a negotiated (or elected) government of national unity?

Switzerland, for example, has a consensus government that reflects parties in parliament, yet Ministers are voted in for a lifetime, hence changes in parliamentary elections are only reflected slowly. Moreso, there is an understanding, that the seven Ministers who serve in government need to stand beyond their mere party interests. The composition of the Swiss government also follows the so-called ‘Miracle Formula’ which is a set of inclusion criteria reflecting the Swiss societal composition, i.e. gender; geographies, and language groups.

As we navigate through an era where political polarisation is increasingly becoming the norm rather than the exception, it is important that as a society we can collectively explore how to foster environments where elections contribute to peacebuilding rather than conflict and ask ourselves where national dialogues can potentially offer a more inclusive platform for addressing the concerns of all societal groups and fostering long-term peace and stability.

I am grateful for the inspiration I got from colleagues at the 6th National Dialogue Conference workshop on the linkage between Elections and National Dialogues, especially Matthias Wevelsiep, Paula Tarvainen, and Hope Chichaya which made me think deeply about the different trends during the 2024 election year.

Report,

A Practical Guide to a Gender-Inclusive National Dialogue

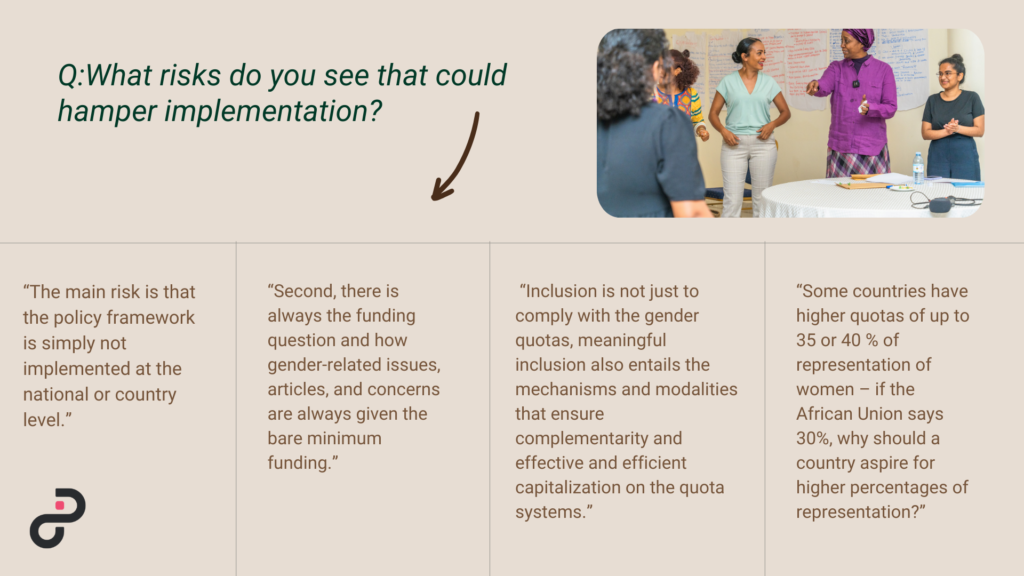

This guide is intended to be a practical resource for anyone preparing, advocating for, or participating in an upcoming or ongoing national dialogue, and it seeks to foster understanding of how to make a national dialogue truly inclusive of women and gender.

May 2023Nick Ross,

Report,

What Makes or Breaks National Dialogues?

This report is based on the National Dialogue research project and its comparative analysis of 17 cases of National Dialogues (1990 – 2014). It aims to contribute to a better understanding of the functions of National Dialogues in peace processes.

October 2017Anne Zachariassen, Cindy Helfer, Thania Paffenholz,

Briefing Note,

What Makes or Breaks National Dialogues?_BN

This briefing note summarises the findings of a research project on National Dialogues and inclusive peace processes commissioned by UNDPA. It is based on a comparative analysis of 17 cases of National Dialogues (1990-2014).

April 2017IPTI,