Our latest report zeroes in on crucial gaps in the Track II Kosovo-Serbia peace process, highlighting the importance of reshaping the process to make engagements more inclusive.

Despite progress in women’s representation in leadership positions, significant barriers still hinder women’s meaningful inclusion in both Track I and Track II peace processes between Kosovo and Serbia.Our joint report Shaping Peace: Women’s Inclusion in the Kosovo Serbia Peace process, written in partnership with the Research Institute of Development and European Affairs and funded by the Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund’s Rapid Response Window, underscores key entry points to advance women’s inclusion, such as promoting local ownership and empowering Kosovo women peacebuilders.

Key insights from the report

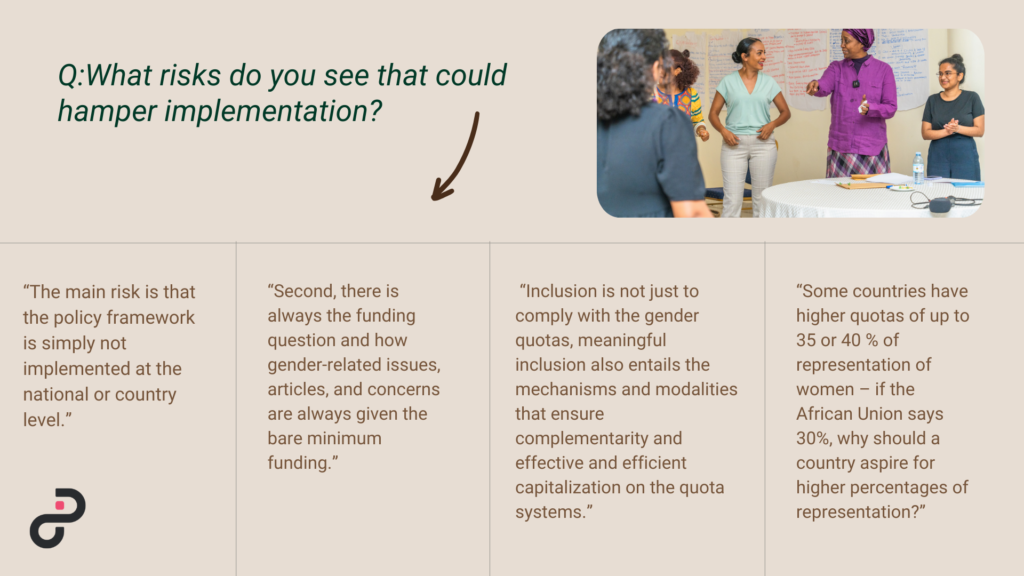

The interview data revealed contrasting perspectives regarding potential solutions to address the commonly recognised deadlock. Across the interviews, what stands out amid this broad spectrum of perspectives is the shared understanding that women have been excluded and that there is a need to enhance their inclusion.

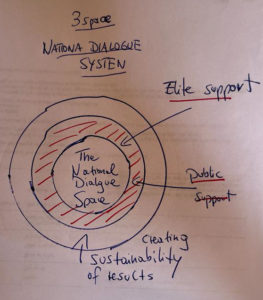

First, peace processes between Kosovo and Serbia are viewed as being in a condition of stalemate, with political stakeholders perceiving them as a platform for unnecessary compromises or a zero-sum game. Others express concerns about weak internal commitments and the diminishing external leverage of the EU, which has spearheaded dialogue efforts aimed at advancing the process. The findings substantiate the notion of the broadly exclusive nature of the process, with many respondents criticising it for being elitist, top-down, and imposed by international actors.

Second, the interviews bring into focus the challenge of meaningful women’s inclusion, particularly in the sense of women being present but not represented. Despite advancements in women’s representation in leadership positions, this progress has failed to translate into broader meaningful inclusion. There is a lack of genuine commitment to a gender-sensitive agenda that is mindful of how women are affected in different situations.

Third, concerning women’s inclusion in Track II, only a limited number of the participants who directly engaged in previous initiatives could identify specific examples of women’s contributions to the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue. Even in the few examples of previous activities, women actors encountered obstacles in recognition. The most prominent process and context-related constraining factors for women’s inclusion in peace processes include underrepresentation in decision-making and formal negotiations, and societal attitudes and expectations pertaining to gender roles in Kosovo.

Furthermore, women’s inclusion in contributing to and monitoring the progress is still lacking. Across those interviewed, consensus exists on the need to reshape the implementation process into a more bottom-up, citizen-centred undertaking. Interview participants seeking new solutions and instruments to improve monitoring and implementation emphasise inclusive joint monitoring, consisting of civil society, women peacebuilders, government, and international representatives. Effective collaboration in separate tracks and across tracks would also benefit from concrete indicators and steps that engage local communities in Kosovo.

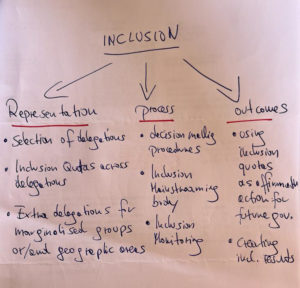

The report identifies the following entry points and options to move forward and enhance women’s inclusion in the Track II peace process and transfer across the tracks:

- Rethinking and changing the approach and strategies on inclusion vis-à-vis domestic and international actors

- Local ownership and an intersectional approach in developing inclusion criteria; ● Promoting trust-building and reconciliation on the grassroots level (and scaling up local engagement)

- Improved transparency and communication between government and civil society in Kosovo

- Developing shared advocacy strategies among Kosovo women peacebuilders

- Establishing consultative mechanisms between Track I and Track II actors

- Changing the scope of the agenda to ensure it is gender sensitive.

The interview respondents underlined that enhancing women’s inclusion is seen by many as being necessary for the sustained successful implementation of the Kosovo-Serbia peace process.

The significance of women’s involvement in advancing stalled processes emerged as a critical focal point for potentially breaking the current stalemate.