Multi-stakeholder political dialogue processes: Lessons from and for the Ethiopian National Dialogue

Inclusive Peace’s Director, Thania Paffenholz, reflects on her recent experience supporting our partners at the forefront of steering and shaping Ethiopia’s national dialogue process.

Author: Thania Paffenholz

I recently had the privilege to spend time with colleagues and friends from Ethiopia who are at the forefront of steering and shaping the Ethiopian national dialogue process. From my engagements last week here are some lessons from and for the Ethiopian and other multi-stakeholder political dialogue processes currently planned.

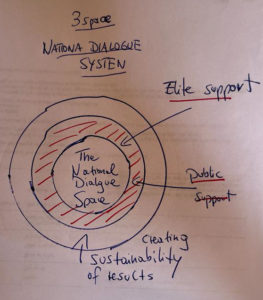

Addressing the dialogue as a three-layered complex system

Once a national dialogue process is planned or started, the focus is mostly on the dialogue space itself; questions are raised like who will participate, how to include marginalised actors, how to link the grassroots with the national process, how to get actors involved that do not want to engage or cannot be engaged out of legal or other reasons, how to access difficult to access geographical areas and how to develop the agenda setting for the process in an inclusive legitimate way. These are all pertinent challenging questions, see more below. What is not addressed sufficiently in most national dialogues are the other spaces outside the immediate dialogue that are equally important for an effective sustainable process.

The first is the political and social context around the dialogue. Comparative research from past national dialogue processes shows that support from key political, economic and societal elites as well as public support for the process are a make or break factors for any dialogue. It is not enough to have elite and public support at the beginning of the process; this support needs to be sustained throughout the process. In Yemen, for example, the dialogue process was very inclusive and decision-making was transparent and democratic. Nevertheless, the dialogue lost elite and public support over time and after the closure of the dialogue in 2014, war broke out that lasted until to date.

The third space for a national dialogue to consider is its sustainability: How can the results of such dialogues be used to shape the future of a peaceful and inclusive society? These questions are mostly left open to the end of the process. Dialogue organisers and participants often feel that there is an automatism between the discussions at the dialogue and its sustainable implementation. However, comparative research shows that the majority of national dialogue results are never implemented. It is thus crucial to shape the dialogue design and procedures in such a way that contributes to future sustainability.

What does this mean? For example, how transparent, inclusive, and democratic the selection of participants and the decision-making procedures will be designed, will determine how this will be applied in future governance procedures. The dialogue needs to pave the way into the future by example. Inclusion quotas for all delegations participating in the dialogue like gender, age, and geography, have been used in the cases of South Africa and Nepal as affirmative action for future government and public institutions. In Nepal, these quotas even permeated public life as they were automatically applied in social settings like associations or schools.

The inclusion challenge

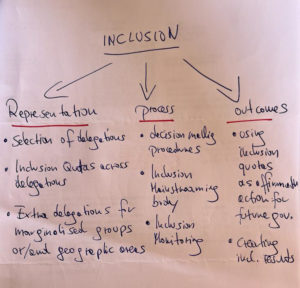

Getting Inclusion right is at the heart of broad-based dialogue processes. However, there is often big confusion around inclusion centred around misunderstandings of the goals and strategies of inclusion. Is inclusion seen as representation, as a process or as an outcome? The simple answer is, that it is all of this, but different strategies and procedures need to be applied for each of these goals.

Inclusion as representation has three dimensions: First, who are the groups and constituencies participating in the dialogue; second, what is the quota system across delegations (the so-called ‘Inclusion formula’) representing the population right large as delegations will nominate or elect their members, they will have to apply a quota system during this process determined from the beginning, i.e. gender – what is the ratio of men and women within the delegations; age; geographic distribution, etc. Third, specific marginalised groups will get an extra delegation. For example, this happened in the Yemeni dialogue where women, youth and representatives from a marginalised geographical area received an extra delegation to ensure that their interests were met.

Second, inclusion as a process means that it is crucial how inclusion is practised during the process, ie. Are selection and decision-making criteria transparent and inclusive, or do they favour some over others? For example, in one of the very representative Somalia Dialogue processes, all decisions were made by a leadership committee comprised only of the big clans.

Third, inclusion as an outcome, it is not only important to have an inclusive process but to design for inclusive sustainable outcomes.

Strategic communication is a lacking essential

Strategic communication is an absent feature of many national dialogues. While operational communication is always practised (press briefings, social media or website information on the process) a holistic proactive strategic communication strategy that is better understood as active marketing of the dialogue, is mostly missing. Why is it important? Public and elite support is essential and can only be achieved with proactive strategic communication that guides all activities, gets the awareness and buy-in of the population and prevents potential conflicts.

Timeframe

Finding the right balance between rushing for results and leaving no one behind is a context-dependent and essential question bothering organisers of national dialogues. If the national dialogue is rushed, it often lacks legitimacy as it does not take sufficient time to get all relevant stakeholders on board or procedures right; if a national dialogue or its preparation is dragged on for too long, there is also a risk of losing public and elite support. Strategic communication is the most important element to counteract these risks in both cases.

Agenda setting

This is a complex task and often part of the national dialogue process at the beginning. The most important is to listen to people and develop an agenda that is legitimate and representative. Important as well is important to consider the mandate of the dialogue and other processes or institutions in the country that might be able to take over and immediately address some agenda points so that they do not have to be dealt with by the national dialogues. Not overloading the agenda to be able to produce implementable results is another important takeaway from other processes.

Armed conflict and national dialogues

National Dialogues often take place when there is still violence in the country. Evidence shows that national dialogues can take place in parallel to violence and there are different ways of including or connecting armed groups to the dialogue process – however, if armed conflicts are managed it is often easier to pursue the dialogue.

Protection, safe spaces and psycho-social support

Another set of overlooked issues in dialogue processes is the protection of participants. Often people take risks in participating in dialogues and their political and physical security needs to be considered when planning the dialogue process. Protection from social media shaming campaigns is a very relevant feature of current processes that is equally overlooked.

Creating the dialogue as a safe space is equally important as is psychosocial support for participants during the entire process as most people are traumatised and need healing and support to be able to participate.

Preparing for a national dialogue is a major task

Next to the political and technical preparations for a dialogue, preparing participants for the dialogue is key. Some groups are often much better prepared than others, which creates inequalities. Hence, systematic capacity building for understanding the dialogue and its functioning, as well as how to strategise for influence and develop joint positions are needed components.

Report,

A Practical Guide to a Gender-Inclusive National Dialogue

This guide is intended to be a practical resource for anyone preparing, advocating for, or participating in an upcoming or ongoing national dialogue, and it seeks to foster understanding of how to make a national dialogue truly inclusive of women and gender.

May 2023Nick Ross,

Report,

What Makes or Breaks National Dialogues?

This report is based on the National Dialogue research project and its comparative analysis of 17 cases of National Dialogues (1990 – 2014). It aims to contribute to a better understanding of the functions of National Dialogues in peace processes.

October 2017Anne Zachariassen, Cindy Helfer, Thania Paffenholz,

Briefing Note,

What Makes or Breaks National Dialogues?_BN

This briefing note summarises the findings of a research project on National Dialogues and inclusive peace processes commissioned by UNDPA. It is based on a comparative analysis of 17 cases of National Dialogues (1990-2014).

April 2017IPTI,