Perpetual Peacebuilding in Northern Ireland

This week marks the 25th anniversary of the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement (GFA) in Northern Ireland, which was signed on 10 April. The specific peace process that gave rise to the GFA, as well as events during the 30 years before the GFA and in the 25 years since are an excellent illustration of how building peace is a perpetual, non-linear process, involving constant negotiation and re-negotiation of the social and political contract, marked by a mixture of progress, resistance, and setbacks.

Paving the way for the GFA: Northern Ireland’s protracted official peace process(es)

During the 30 or so years of conflict known as “the Troubles”, there was a series of formal attempts at reaching a constitutional settlement to reconcile loyalist (unionist) and republican (nationalist) divides. While they did not resolve any major substantive issues, they did lay the groundwork for the GFA process by improving and institutionalising Anglo–Irish cooperation at the inter-governmental level, and reaching a consensus on the main topics and discussion strands future negotiations would address, including devolved democratic institutions in Northern Ireland, formal bodies dedicated to North–South relations (Northern Ireland and Ireland), and structures dedicated to institutional East–West cooperation (the United Kingdom and Ireland). The two Governments outlined these themes in a comprehensive set of proposals, the “Frameworks Document,” which served as a blueprint for the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement.

The GFA process itself was also far from plain sailing. The IRA’s attack in London in February 1996, ending its ceasefire, meant that while Sinn Féin still contested the election to the Northern Ireland Forum for Political Dialogue it was initially barred from attending the multi-party talks. Elections in the UK in May 1997 and in Ireland in June 1997 catalysed the peace process: the new Labour Government in the UK was better placed to temper the suspicions of nationalists in Northern Ireland about the UK Government’s commitment to the process, and it had a more solid parliamentary base for engagement in the process; the new Irish Fianna Fáil government was in a better position to deal decisively with the republican movement due to its traditional association with the ideals of republicanism. In July 1997, the IRA announced the renewal of its ceasefire, prompting an invitation to Sinn Féin to join the multi-party talks. Despite a brief withdrawal of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), substantive negotiations began in October 1997. After all-night discussions and a 17- hour extension of the deadline, the talks resulted in the signing of the GFA on 10 April 1998.

The political Rubik’s Cube: navigating the post-GFA political landscape

The GFA is a multifaceted agreement dealing with issues relating to sovereignty, governance, decommissioning and security, policing and the judiciary, and discrimination. In addition to establishing formal institutions across these thematic areas, it also established a devolved system of government in Northern Ireland comprising a legislature – the Northern Ireland Assembly (“Stormont”), and a power-sharing executive – the Executive Committee – run by a duumvirate appointed by the two largest parties in the Assembly.

Yet, the political settlement ushered in by the GFA has proved highly contested; Northern Irish politics has remained extremely polarised, and there have been multiple collapses of the executive (which has now not functioned for over a third of its lifespan) and suspensions of the Assembly since 1998. Renewed talks in 2006 attempted to provide a road map (the 2007 St Andrews Agreement) towards addressing the major bones of contention, chiefly the acceptance of devolved policing and the rule of law for Sinn Féin, and the acceptance of power sharing for the DUP. The power-sharing arrangement subsequently was slightly more stable, until circumstances – notably the result of the referendum in June 2016, on the United Kingdom leaving the European Union – once again muddied the constitutional waters. The power-sharing arrangement was suspended for three years in 2017 following a crisis over a renewable energy payments scandal, before being uneasily restored. Brexit provoked another collapse in early 2022 that is yet to be resolved; whether the February 2023 Windsor Framework for post-Brexit trading arrangements can do so remains to be seen.

Healing a divided and changing society

The inherent weaknesses in the power-sharing arrangement are both rooted in and reflect the fact that societal tensions are yet to be fully reconciled. While efforts at peace-making and peacebuilding in Northern Ireland have significantly attenuated generations of violent inter-communal division in Northern Ireland, ongoing sectarian tension – including a lack of integration and cohabitation amongst communities and, in recent years, disputes over the use of flags and symbols, parades and marches that showcase sectarian identities, welfare and police reforms, the arrest of Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams in 2014, and the Irish National Language Act – is both a symptom and a cause of ongoing distrust between loyalists and republican communities.

Caption: The persistence of about 60 peace walls, which physically separate loyalist and republican neighbourhoods in various cities, bear witness to the ongoing divisions in Northern Irish society. Yet, there has also been a marked recent shift in political and societal attitudes and priorities beyond sectarianism. The electoral success of both Sinn Féin and the non-sectarian Alliance Party in the 2022 Stormont elections are the manifestation of the Northern Irish population attaching greater importance to (universal) issues like education, healthcare, the welfare system, and economic considerations – chiefly inflation and the cost-of-living crisis – than to sectarian issues and Northern Ireland’s constitutional status. Polls in 2022 found that 21% Northern Ireland’s citizens consider themselves as “Northern Irish” rather than “British” or “Irish”.

Yet, there has also been a marked recent shift in political and societal attitudes and priorities beyond sectarianism. The electoral success of both Sinn Féin and the non-sectarian Alliance Party in the 2022 Stormont elections are the manifestation of the Northern Irish population attaching greater importance to (universal) issues like education, healthcare, the welfare system, and economic considerations – chiefly inflation and the cost-of-living crisis – than to sectarian issues and Northern Ireland’s constitutional status. Polls in 2022 found that 21% Northern Ireland’s citizens consider themselves as “Northern Irish” rather than “British” or “Irish”.

This can partly be explained by a (natural) generational shift; younger people in the country who didn’t grow up during the Troubles seemingly view their aspirations and the challenges they face through other lenses than a purely or even principally sectarian one. All of this shows that what peace means and looks like in a specific context is a constantly moving target.

Building lasting peace is a society-wide endeavour

Northern Irish society during the Troubles has been widely referred to as a state of “armed patriarchy” underpinned by conservative, masculinised values and discourse of nationalism and religion.

In spite of that, women were heavily involved in civil rights and particularly local community work during the Troubles, advocating for peace and social change. Women’s groups succeeded in securing the participation of a dedicated women’s caucus – the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition – in the track one negotiations. Women successfully advocated for the inclusion of language and provisions in the GFA on equal opportunity, women’s rights to equal political participation, social inclusion, reconciliation and the needs of victims of violence, integrated education and mixed housing, and for a Civic Forum to engage with a broad range of stakeholders on the implementation of the GFA. Women were also included in official consultations, played a key role in the “yes” campaign that succeeded in ratifying the GFA by referendum, and were involved in GFA-mandated commissions.

Faith-based actors have also made a major contribution to building peace in Northern Ireland. During the Troubles, in spite of the sectarian divide, which was partly both crystalised around and perpetuated by socio-cultural religious organisations like the Orange Order, a number of Protestant and Catholic actors mobilised for peace. This included organising large scale Peace Marches, acting as mediators between militants, and advocating for and facilitating ceasefires. They also worked to build trust and understanding within and between different sectarian groups through hosting meetings between paramilitary leaders on both sides of the conflict. Faith-based actors have been involved in the implementation of the GFA and have continued efforts to foster social reconciliation and healing, including through creating and facilitating spaces where people who identify as loyalist or republican can come together and have uncomfortable, but necessary conversations to humanise one another.

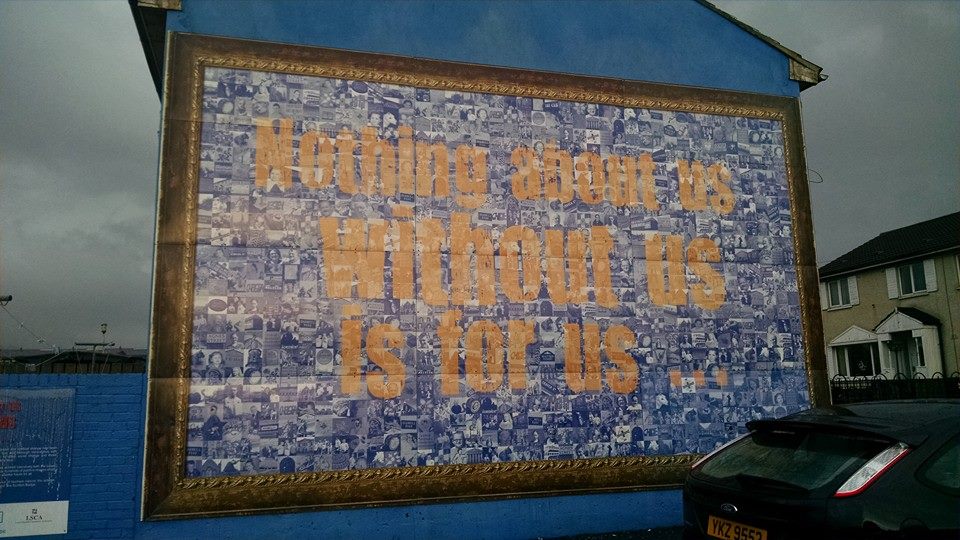

Caption: Peace walls decorated with hopeful murals are just one example of the myriad ways in which communities in Northern Ireland are trying to reconcile their differences and build a shared peaceful future

We know from evidence and experience that society-wide involvement in building peace is crucial to making peace inclusive and sustainable. Bottom-up initiatives and spaces for societal involvement take on even greater importance in contexts like Northern Ireland, where the formal political arena is deadlocked. Recent and current examples, ranging from consultative bodies the Civic Forum and the British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly, to existing inter-sectarian civic spaces such as the Suffolk and Lenadoon Interface Group or the 174 Trust provide a blueprint to consolidate and expand. Doing so is a crucial aspect of reimagining and diversifying the ways we understand and undertake peacemaking and peacebuilding, which is essential to making sure these processes are an integral part of – rather than separated from – the arc of a society’s changing development, and to ensuring that that arc bends towards a peaceful, just, and inclusive future.

————————————————————-

This blog post was written by Alexander Bramble and Philip Poppelreuter

Check out our case study and our infographic on women in the 1996-1998 Northern Ireland peace process, our digital story on faith-based actors’ peacebuilding work in Northern Ireland, and our blog post on Perpetual Peacebuilding.

Photos: “File:Nothing with us.jpg” by Michael Lovito is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, “Peace in Northern Ireland – geograph.org.uk – 3551004” by Oliver Dixon is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. “Belfast Murals – Sandy Row (5702530038)” by William Murphy from Dublin, Ireland is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. “File:Peace Line, Belfast – geograph – 1254138.jpg” by Ross is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Case Study,

Women in Peace and Transition Processes: Northern Ireland (1996–1998)

This case study analyses women’s influence in Northern Ireland’s Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement (1996-1998).

December 2018Alexander Bramble,

Infographic,

Infographic: Women’s role in Northern Ireland’s Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement (1996-1998)

This infographic analyses women’s influence in Northern Ireland’s Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement (1996-1998).

December 2018IPTI,